Dickens, Charles

"Dickens" redirects here. For other uses, see Dickens (disambiguation).

| Charles Dickens |

|

| Born |

Charles John Huffam Dickens

7 February 1812(1812-02-07)

Landport, Portsmouth,

England |

| Died |

9 June 1870(1870-06-09) (aged 58)

Gad's Hill Place, Higham, Kent,

England |

| Cause of death |

Stroke |

| Resting place |

Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey |

| Nationality |

British |

| Other names |

Boz |

| Citizenship |

UK |

| Occupation |

Writer |

| Years active |

1833–1870 |

| Notable works |

Sketches by Boz, The Old Curiosity Shop, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, Barnaby Rudge, A Christmas Carol, Martin Chuzzlewit, A Tale of Two Cities, David Copperfield, Great Expectations, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Hard Times, Our Mutual Friend, The Pickwick Papers |

| Spouse |

Catherine Thomson Hogarth |

| Children |

Charles Dickens, Jr., Mary Dickens, Kate Perugini, Walter Landor Dickens, Francis, Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens, Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens, Henry Fielding Dickens, Dora Annie Dickens, and Edward Dickens |

| Parents |

John Dickens

Elizabeth Dickens |

| Signature |

|

Charles John Huffam Dickens (pronounced /ˈtʃɑrlz ˈdɪkɪnz/; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was the most popular English novelist of the Victorian era and he remains popular, responsible for some of English literature's most iconic characters.[1]

Many of his novels, with their recurrent concern for social reform, first appeared in magazines in serialised form, a popular format at the time. Unlike other authors who completed entire novels before serialisation, Dickens often created the episodes as they were being serialized. The practice lent his stories a particular rhythm, punctuated by cliffhangers to keep the public looking forward to the next instalment.[2] The continuing popularity of his novels and short stories is such that they have never gone out of print.[3]

His work has been praised for its mastery of prose and unique personalities by writers such as George Gissing, Leo Tolstoy and G. K. Chesterton, though others, such as Henry James and Virginia Woolf, criticised it for sentimentality and implausibility.[4]

Life

Early years

2 Ordnance Terrace, Chatham, Dickens's home 1817–1822

Having spent the first three years of his life in Portsmouth, Hampshire, the family moved to London in 1815. His early years seem to have been idyllic, although he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy".[5] He spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, especially the picaresque novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. He spoke, later in life, of his poignant memories of childhood, and of his near photographic memory of the people and events, which he used in his writing. His father's brief period as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office afforded Charles a few years' private education at William Giles's School, in Chatham.[6]

This period came to an abrupt end when John Dickens spent beyond his means and was imprisoned in the Marshalsea debtor's prison in Southwark, London. Shortly afterwards, the rest of his family joined him - except Charles, who boarded with family friend Elizabeth Roylance in Camden Town.[7] Mrs. Roylance was "a reduced old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs. Pipchin", in Dombey and Son. Later, he lived in a "back-attic...at the house of an insolvent-court agent...in Lant Street in The Borough...he was a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman, with a quiet old wife; and he had a very innocent grown-up son; these three were the inspiration for the Garland family in The Old Curiosity Shop.[8]

The Marshalsea around 1897, after it had closed

On Sundays, Dickens and his sister Fanny, allowed out from the Royal Academy of Music, spent the day at the Marshalsea.[9] (Dickens later used the prison as a setting in Little Dorrit.) To pay for his board and to help his family, Dickens began working ten-hour days at Warren's Blacking Warehouse, on Hungerford Stairs, near the present Charing Cross railway station. He earned six shillings a week pasting labels on shoe polish. The strenuous - and often cruel - work conditions made a deep impression on Dickens, and later influenced his fiction and essays, forming foundation of his interest in the reform of socio-economic and labour conditions, the rigours of which he believed were unfairly borne by the poor. As told to John Forster (from The Life of Charles Dickens):

A 1904 artist's impression of Dickens in the shoe-polish factory

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary's shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist.[8]

After only a few months in Marshalsea, John Dickens' paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him the sum of £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was granted release from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors, and he and his family left Marshalsea for the home of Mrs. Roylance.

Although Dickens eventually attended the Wellington House Academy in North London, his mother Elizabeth Dickens did not immediately remove him from the boot-blacking factory. 'The incident must have done much to confirm Dickens's determined view that a father should rule the family, a mother find her proper sphere inside the home. "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." His mother's failure to request his return was no doubt a factor in his demanding and dissatisfied attitude towards women.'[10] Resentment stemming from his situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, David Copperfield:[11] "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!" The Wellington House Academy was not a good school. 'Much of the haphazard, desultory teaching, poor discipline punctuated by the headmaster's sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr. Creakle's Establishment in David Copperfield.'[12]

Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, of Holborn Court, Gray's Inn, as a junior clerk from May 1827 to November 1828. Then, having learned Gurneys system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter. A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors' Commons, and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years.[13] This education informed works such as Nicholas Nickleby, Dombey and Son, and especially Bleak House—whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public, and was a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens's own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to "go to law".

In 1830, Dickens met his first love, Maria Beadnell, thought to have been the model for the character Dora in David Copperfield. Maria's parents disapproved of the courtship and effectively ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris.

Journalism and early novels

In 1833, Dickens' first story, A Dinner at Poplar Walk was published in the London periodical, Monthly Magazine. The following year he rented rooms at Furnival's Inn becoming a political journalist, reporting on parliamentary debate and travelling across Britain to cover election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. His journalism, in the form of sketches in periodicals, formed his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz, published in 1836. This led to the serialisation of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, in March 1836. He continued to contribute to and edit journals throughout his literary career.

An 1839 portrait of a young Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise

In 1836, Dickens accepted the job of editor of Bentley's Miscellany, a position he held for three years, until he fell out with the owner. At the same time, his success as a novelist continued, producing Oliver Twist (1837–39), Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39), The Old Curiosity Shop and, finally, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty as part of the Master Humphrey's Clock series (1840–41)—all published in monthly instalments before being made into books. Dickens had a pet raven named Grip which he had stuffed when it died in 1841. (it is now at the Free Library of Philadelphia).[14]

On 2 April 1836, he married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1816 – 1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle. After a brief honeymoon in Chalk, Kent, they set up home in Bloomsbury. They had ten children:[15]

- Charles Culliford Boz Dickens (C. C. B. Dickens), later known as Charles Dickens, Jr., editor of All the Year Round, and author of the Dickens's Dictionary of London (1879).

- Mary Dickens

- Kate Macready Dickens

- Walter Landor Dickens

- Francis Jeffrey Dickens

- Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens

- Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens

- Sir Henry Fielding Dickens

- Dora Annie Dickens

- Edward Dickens

Dickens and his family lived at 48 Doughty Street, London, (on which he had a three year lease at £80 a year) from 25 March 1837 until December 1839. Dickens's younger brother Frederick and Catherine's 17 year old sister Mary moved in with them. Dickens became very attached to Mary, and she died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837. She became a character in many of his books, and her death is fictionalised as the death of Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop.[16]

First visit to America

In 1842, Dickens and his wife made his first trip to the United States and Canada, a journey which was successful in spite of his support for the abolition of slavery. It is described in the travelogue American Notes for General Circulation and is also the basis of some of the episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit. Dickens includes in Notes a powerful condemnation of slavery,[17] with "ample proof" of the "atrocities" he found.[18] He called upon President John Tyler at the White House.[19]

During his visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures, raising support for copyright laws, and recording many of his impressions of America. He met such luminaries as Washington Irving and William Cullen Bryant. On 14 February 1842, a Boz Ball was held in his honour at the Park Theater, with 3,000 guests. Among the neighbourhoods he visited were Five Points, Wall Street, The Bowery, and the prison known as The Tombs.[20] At this time Georgina Hogarth, another sister of Catherine, joined the Dickens household, now living at Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone, to care for the young family they had left behind.[21] She remained with them as housekeeper, organiser, adviser and friend until her brother-in-law's death in 1870.

Shortly thereafter, he began to show interest in Unitarian Christianity, although he remained an Anglican for the rest of his life.[22] Dickens's work continued to be popular, especially A Christmas Carol written in 1843, which was reputedly a potboiler written in a matter of weeks to meet the expenses of his wife's fifth pregnancy. After living briefly abroad in Italy (1844) and Switzerland (1846), Dickens continued his success with Dombey and Son (1848) and David Copperfield (1849–50).

Philanthropy

In May 1846, Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens about setting up a home for the redemption of "fallen" women. Coutts envisioned a home that would differ from existing institutions, which offered a harsh and punishing regimen for these women, and instead provide an environment where they could learn to read and write and become proficient in domestic household chores so as to re-integrate them into society. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named Urania Cottage, in the Lime Grove section of Shepherds Bush. He became involved in many aspects of its day-to-day running, setting the house rules, reviewing the accounts and interviewing prospective residents, some of whom became characters in his books. He would scour prisons and workhouses for potentially suitable candidates and relied on friends, such as the Magistrate John Hardwick to bring them to his attention. Each potential candidate was given a printed invitation written by Dickens called ‘An Appeal to Fallen Women’[23], which he signed only as ‘Your friend’. If the woman accepted the invitation, Dickens would personally interview her for admission.[24][25] All of the women were required to emigrate following their time at Urania Cottage. In research published in 2009, the families of two of these women were identified, one in Canada and one in Australia. It is estimated that about 100 women graduated between 1847 and 1859.[26]

Dickens painted by Ary Scheffer, 1855. Dickens wrote John Forster of the experience: "I can scarcely express how uneasy and unsettled it makes me to sit, sit, sit, with

Little Dorrit on my mind."

In late November 1851, Dickens moved into Tavistock House[27] where he would write Bleak House (1852–53), Hard Times (1854) and Little Dorrit (1857). It was here he got up the amateur theatricals which are described in Forster's Life.

Photograph of the author, c. 1852

Middle years

In 1856, his income from his writing allowed him to buy Gad's Hill Place in Higham, Kent. As a child, Dickens had walked past the house and dreamed of living in it. The area was also the scene of some of the events of Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1 and this literary connection pleased him.

In 1857, Dickens hired professional actresses for the play The Frozen Deep, which he and his protégé Wilkie Collins had written. With one of these, Ellen Ternan, Dickens formed a bond which was to last the rest of his life. He then separated from his wife, Catherine, in 1858 - divorce was still unthinkable for someone as famous as he was.

During this period, whilst pondering about giving public readings for his own profit, Dickens was approached by Great Ormond Street Hospital to help it survive its first major financial crisis through a charitable appeal. Dickens, whose philanthropy was well-known, was asked to preside by his friend, the hospital's founder Charles West. He threw himself into the task, heart and soul[28] (a little known fact is that Dickens reported anonymously in the weekly The Examiner in 1849 to help mishandled children and wrote another article to help publicise the hospital's opening in 1852).[29] On 9 February 1858, Dickens spoke at the hospital's first annual festival dinner at Freemasons' Hall and later gave a public reading of A Christmas Carol at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church hall. The events raised enough money to enable the hospital to purchase the neighbouring house, No. 48 Great Ormond Street, increasing the bed capacity from 20 to 75.[30]

That summer of 1858, after separating from his wife,[31] Dickens undertook his first series of public readings in London for pay which ended on 22 July. After 10 days rest, he began a gruelling and ambitious tour through the English provinces, Scotland and Ireland, beginning with a performance in Clifton on 2 August and closing in Brighton, more than three months later, on 13 November. Altogether he read eighty-seven times, on some days giving both a matinée and an evening performance.[32]

Major works, A Tale of Two Cities (1859); and Great Expectations (1861) soon followed and would prove resounding successes. During this time he was also the publisher and editor of, and a major contributor to, the journals Household Words (1850–1859) and All the Year Round (1858–1870).

In early September 1860, in a field behind Gad's Hill, Dickens made a great bonfire of nearly his entire correspondence. Only those letters on business matters were spared. Since Ellen Ternan burned all of his letters as well, the dimensions of the affair between the two were unknown until the publication of Dickens and Daughter, a book about Dickens's relationship with his daughter Kate, in 1939. Kate Dickens worked with author Gladys Storey on the book prior to her death in 1929, and alleged that Dickens and Ternan had a son who died in infancy, though no contemporary evidence exists.[33] On his death, Dickens settled an annuity on Ternan which made her a financially independent woman. Claire Tomalin's book, The Invisible Woman, set out to prove that Ternan lived with Dickens secretly for the last 13 years of his life, and was subsequently turned into a play, Little Nell, by Simon Gray.

In the same period, Dickens furthered his interest in the paranormal, so much that he was one of the early members of The Ghost Club.[34]

Franklin incident

A recurring theme in Dickens's writing reflected the public's interest in Arctic exploration: the heroic friendship between explorers John Franklin and John Richardson gave the idea for A Tale of Two Cities, The Wreck of the Golden Mary and the play The Frozen Deep.[35]

After Franklin died in unexplained circumstances on an expedition to find the North West Passage, Dickens wrote a piece in Household Words defending his hero against the discovery in 1854, some four years after the search began, of evidence that Franklin's men had, in their desperation, resorted to cannibalism.[36] Without adducing any supporting evidence he speculates that, far from resorting to cannibalism amongst themselves, the members of the expedition may have been "set upon and slain by the Esquimaux ... We believe every savage to be in his heart covetous, treacherous, and cruel."[36] Although publishing in a subsequent issue of Household Words a defence of the Esquimaux, written by John Rae, one of Franklin's rescue parties, who had actually visited the scene of the supposed cannibalism, Dickens refused to alter his view.[37]

Last years

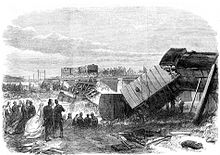

Crash scene after the Staplehurst rail crash

On 9 June 1865,[38] while returning from Paris with Ternan, Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash. The first seven carriages of the train plunged off a cast iron bridge under repair. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was the one in which Dickens was travelling. Dickens tried to help the wounded and the dying before rescuers arrived. Before leaving, he remembered the unfinished manuscript for Our Mutual Friend, and he returned to his carriage to retrieve it. Typically, Dickens later used this experience as material for his short ghost story The Signal-Man in which the central character has a premonition of his own death in a rail crash. He based the story around several previous rail accidents, such as the Clayton Tunnel rail crash of 1861.

Dickens managed to avoid an appearance at the inquest, to avoid disclosing that he had been travelling with Ternan and her mother, which would have caused a scandal. Although physically unharmed, Dickens never really recovered from the trauma of the Staplehurst crash, and his normally prolific writing shrank to completing Our Mutual Friend and starting the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Much of his time was taken up with public readings from his best-loved novels. Dickens was fascinated by the theatre as an escape from the world, and theatres and theatrical people appear in Nicholas Nickleby. The travelling shows were extremely popular. In 1866, a series of public readings were undertaken in England and Scotland. The following year saw more readings in England and Ireland.

Photograph of Dickens taken by Jeremiah Gurney & Son, New York, 1867

Second visit to America

On 9 November 1867, Dickens sailed from Liverpool for his second American reading tour. Landing at Boston, he devoted the rest of the month to a round of dinners with such notables as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his American publisher James Thomas Fields. In early December, the readings began and Dickens spent the month shuttling between Boston and New York. Although he had started to suffer from what he called the "true American catarrh", he kept to a schedule that would have challenged a much younger man, even managing to squeeze in some sleighing in Central Park. In New York, he gave 22 readings at Steinway Hall between 9 December 1867 and 18 April 1868, and four at Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims between 16 January and 21 January 1868. During his travels, he saw a significant change in the people and the circumstances of America. His final appearance was at a banquet the American Press held in his honour at Delmonico's on 18 April, when he promised to never denounce America again. By the end of the tour, the author could hardly manage solid food, subsisting on champagne and eggs beaten in sherry. On 23 April, he boarded his ship to return to Britain, barely escaping a Federal Tax Lien against the proceeds of his lecture tour.[20]

Farewell readings

Between 1868 and 1869, Dickens gave a series of "farewell readings" in England, Scotland, and Ireland, until he collapsed on 22 April 1869, at Preston in Lancashire showing symptoms of a mild stroke.[39] After further provincial readings were cancelled, he began work on his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. In an opium den in Shadwell, he witnessed an elderly pusher known as "Opium Sal", who subsequently featured in his mystery novel.

Poster promoting a reading by Dickens in Nottingham dated Feb. 4, 1869; two months before he suffered a mild stroke

When he had regained sufficient strength, Dickens arranged, with medical approval, for a final series of readings at least partially to make up to his sponsors what they had lost due of his illness. There were to be twelve performances, running between 11 January and 15 March 1870, the last taking place at 8:00 pm at St. James's Hall in London. Although in grave health by this time, he read A Christmas Carol and The Trial from Pickwick. On 2 May, he made his last public appearance at a Royal Academy Banquet in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, paying a special tribute to the passing of his friend, illustrator Daniel Maclise.[40]

Death

On 8 June 1870, Dickens suffered another stroke at his home, after a full day's work on Edwin Drood. The next day, on 9 June, and five years to the day after the Staplehurst crash, he died at Gad's Hill Place never having regained consciousness. Contrary to his wish to be buried at Rochester Cathedral "in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner", he was laid to rest in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey.[41] A printed epitaph circulated at the time of the funeral reads: "To the Memory of Charles Dickens (England's most popular author) who died at his residence, Higham, near Rochester, Kent, 9 June 1870, aged 58 years. He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England's greatest writers is lost to the world."[42] Dickens's last words, as reported in his obituary in The Times were alleged to have been:

Be natural my children. For the writer that is natural has fullfilled all the rules of art.[43]

On Sunday, 19 June 1870, five days after Dickens's interment in the Abbey, Dean Arthur Penrhyn Stanley delivered a memorial elegy, lauding "the genial and loving humorist whom we now mourn", for showing by his own example "that even in dealing with the darkest scenes and the most degraded characters, genius could still be clean, and mirth could be innocent." Pointing to the fresh flowers that adorned the novelist's grave, Stanley assured those present that "the spot would thenceforth be a sacred one with both the New World and the Old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue."[44]

Dickens's will stipulated that no memorial be erected to honour him. The only life-size bronze statue of Dickens, cast in 1891 by Francis Edwin Elwell, is located in Clark Park in the Spruce Hill neighbourhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the United States. The couch on which he died is preserved at the Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth.

Literary style

Dickens loved the style of 18th century Gothic romance,[citation needed] although it had already become a target for parody.[citation needed] One "character" vividly drawn throughout his novels is London itself. From the coaching inns on the outskirts of the city to the lower reaches of the Thames, all aspects of the capital are described over the course of his body of work.

His writing style is florid and poetic, with a strong comic touch. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery—he calls one character the "Noble Refrigerator"—are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats, or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens's acclaimed flights of fancy. Many of his characters' names provide the reader with a hint as to the roles played in advancing the storyline, such as Mr. Murdstone in the novel David Copperfield, which is clearly a combination of "murder" and stony coldness. His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism.

Characters

'Dickens' Dream' by Robert William Buss, portraying Dickens at his desk at Gads Hill Place surrounded by many of his characters

Dickens is famed for his depiction of the hardships of the working class, his intricate plots, his sense of humour. But he is perhaps most famed for the characters he created. His novels were heralded early in his career for their ability to capture the everyday man and thus create characters to whom readers could relate. Beginning with The Pickwick Papers in 1836, Dickens wrote numerous novels, each uniquely filled with believable personalities and vivid physical descriptions. Dickens's friend and biographer, John Forster, said that Dickens made "characters real existences, not by describing them but by letting them describe themselves."[45]

Dickensian characters—especially their typically whimsical names—are among the most memorable in English literature. The likes of Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Jacob Marley, Bob Cratchit, Oliver Twist, The Artful Dod